‘We are not engaged in a war of ambition, or I should not have been here. Every man should be content to serve in that station in which he can be most useful. I have but one object in view…the success of the cause; and God can witness how cheerfully I would lay down my life to secure it’>

(Hugh Mercer, c.1775-7. In Goolrick 1906: 39; cf. Thomas 1837: 572-3)

1 [Image: Hugh Mercer statue, Fredericksburg, Virginia, by Justinandsarah]

I confess: I had never heard of the remarkable adventures of Brigadier-General Hugh Mercer, M.D. – Scots Culloden veteran, friend of George Washington, and 'forgotten hero’ of the American Revolution – before @LoveArchaeology Twitter led me to him. Apparently described as the 'bravest of the brave’ by his Revolutionary colleagues (Embrey 1937: 119), three biographies have been devoted to his life,yet the most recent dates from 1975, and his Wikipedia entry is headed by the foreboding ’needs additional citations for verification’. Even John Trumbull’s sketch of 'Hugh Mercer 'on Wikipedia is actually that of Mercer’s son, taken in April 1791 as a posthumous study for his father’s portrait.

2 [Image: Hugh Mercer entry, Wikipedia]

I wanted to know more, but time and logistical constraintsmeant that I had to rely on online sources. What could be achieved with this

methodology?

Madness in the Method

What follows is Hugh Mercer’s story, or, to be more accurate,

the one which can be found on the internet. It is an exercise in how tweets can

stimulate interest in history and the limitations of web-based down-the-rabbit-hole

research. (Or paraphrasing Wikipedia and

some fact-checking, whatever).

Conceived originally as a sort of Wikipedia+, with added

archaeology, I got drawn into questions concerning the veracity of some of the

legends that have accreted to Mercer. Denied physical biographies by lack of

access and my internet-only methodology – and relying on the sometimes un-footnoted

transcriptions of those biographies I had – it may have only served to muddy

already murky waters, but I hope it serves to reignite interest in my

subject.

Where available, hyperlinks serve as my footnotes, and I

have placed the archaeological background to sites associated with Mercer in

discrete sections marked by the Love Archaeology logo:

I now present a brief summary of Hugh Mercer’s adventures (in

case you want out early).

The Life of Hugh Mercer:

From Bonnie Prince Charlie to George Washington

3 [Image: Hugh

Mercer plaque, Aberdeen, Aberdeen City Council]

All sources agree that Hugh Mercer was born to the Reverend

William Mercer and Ann Munro in the Scottish coastal parish of Pitsligo,

Aberdeenshire, in 1726. Mercer then took

a degree in the Arts in 1744 at Marischal College in Aberdeen, before going

on to qualify as a medical doctor by 1745/6.

Yet, on January 3, 1777, Mercer found himself an American Brigadier-General

of the Revolutionary Continental

Army. That day would end with him being horrifically

wounded in hand-to-hand combat at the Battle of Princeton,

New Jersey, by Regulars (i.e., British Army soldiers) who had mistaken him for

his close friend, George Washington. Although attended to by another American Founding

Father, Dr. Benjamin

Rush (who had also studied medicine in Scotland), Mercer died in agony nine

days later.

Ironically, Mercer had previously served heroically and to

great acclaim with British armed

forces in America during the French

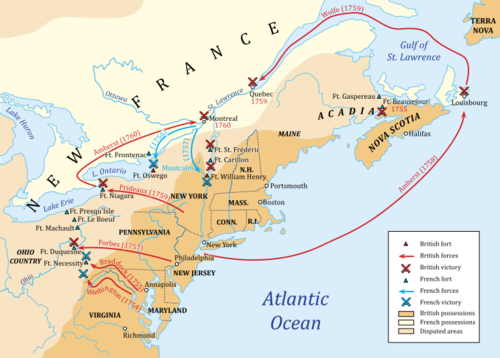

and Indian War (1754-1761), the name given to the North American theatre of

the Seven Years’ War.

This worldwide conflict – effectively the first world war – pitted

the global empires of France and Britain against each other, often in alliances

with the other European powers and indigenous peoples of the lands they

claimed.

Mercer had arrived in the British colonies of North America

in 1747, working as a frontier medic in the dangerous and fluid borderlands of

western Pennsylvania that abutted Native American and French territories. His

desire for remoteness is likely explained by a simple fact: Mercer left Scotland

when he did because he was a Jacobite outlaw, on the run from the British Army

he had faced as a young surgeon’s assistant under Bonnie Prince Charlie at the

Battle of Culloden in April 1746.

Jacobite rebel, American frontier doctor, friend of Founding

Fathers, General, Revolutionary martyr – he was even the great-great-

great-grandfather of General George S. Patton – Mercer’s story deserves to

be rescued from relative obscurity, not least in his native

Scotland.

Use With Caution: An Internet Literature Review

Mercer was a fundamentally impressive figure, but we must

guard against the hero-worship which can over-burnish his legend. With this in

mind, we note that the internet – see Wikipedia’s

references – relies fairly heavily on an online transcription John T.

Goolrick’s 1906 book,

which has the snappy title:

'The life of General Hugh Mercer: with brief sketches of

General George Washington, John Paul Jones, General George Weedon, James Monroe

and Mrs. Mary Ball Washington, who were friends and associates of General

Mercer at Fredericksburg: also a sketch of Lodge no. 4, A.F. and A.M., of which

Generals Washington and Mercer were members: and a genealogical table of the

Mercer family’.

It is very much of its time, and has been equally praised

and criticized over the intervening years:

'John T. Goolrick, The

Life of General Hugh Mercer (N.Y. and

Washington, 1906) and Joseph M. Waterman, With Sword and Lancet: The Life

of General Hugh Mercer (Richmond, Va., 1941) contain some useful facts, but they are always uncritical, often

inaccurate, and must be used with caution’

As this quotation (Bell

1997: 448, n.1) suggests, Goolrick veers fairly uncritically toward

hagiography, but he seems, nevertheless, to use a wide range of primary

sources, many of which seem to check out. It must be noted, however, that I

point out where primary sources quoted elsewhere on the internet contradict

some of the more optimistic spin Goolrick applies to his (and our) hero.

I was unable to locate an Internet transcription of Waterman’s

'With Sword and Lancet’ (1941),

although a scathing 1942 review by H.E. Wildes can be read here. Wildes

criticized Waterman’s 'sketchy’ use of documents and 'paucity of material’,

adding that Goolrick’s book remained the best in the field:

'Scotch-born Hugh

Mercer, surgeon, veteran of Culloden and of Braddock’s expedition, hero of

Kittanning and of Trenton, promoter, land speculator and leader of inspiring

genius, deserves a real biography. His life was rich in incident and sparkling

with excitement; his personality was appealing and dynamic. Few would, however,

guess from this biography that Mercer merited his wide acclaim’ .

Thanks to Google Books, I have also had (partial) access to

some pages of Alvin T. Embrey’s ’History of Fredericksburg, Virginia’

(1937), which corresponds, at least in those parts I can access, to Goolrick.

Embrey had access – which can be independently

corroborated – to primary documents like Mercer’s Will, but was another

huge admirer of the Scot: his chapter on Mercer is subtitled ’The Bravest of the Brave’, a sobriquet

apparently bestowed upon him by his fellow American officers during the

Revolutionary War (although I cannot find any corroboration of this at the time

of writing).

Beyond a few tantalizing fragments, I have not been able to find

a transcription of Frederick English’s 1975

biography, ’General Hugh Mercer,

Forgotten Hero of the American Revolution’, but the book can be purchased

online. For what it’s worth, Mercer’s Wikipedia entry

did not list or reference it (at least, it wasn’t at the time of writing).

My own list of sources can be found at the end of this

article – Mercer appears several times in pen-portrait form in short chapters

that I could access via Google Books – but I must note here the excellence of

the late Whitfield J. Bell’s ’Patriot Improvers: 1743-1768’

(1997), the footnotes and quotations of contemporary letters of which

significantly enriched my account.

As would have been predicted, the internet is an amazing and

evolving resource, but is no substitute for being able to access primary

documents through the footnotes of books. What follows, then, is the Life of

Hugh Mercer for which the web-based evidence seems legit (and that’s all).

Scottish Rebel: Hugh the Jacobite

Battlefield Surgeon (1746)

4 [Image: Culloden, NTS]

The literature is particularly sparse for Mercer’s formative

years in Scotland: indeed, none of the sources know very much about his life

before 1756 – I have seen few references to verifiable documents like parish

records, and one possible university reference – but his approximate date and

place of birth, names of parents, and his being at university between c.1740

and c.1744 are accepted by all.

At the age of 20, it seems that Mercer joined the Jacobite army

of the Bonnie Prince, Charles

Edward Stuart, as a surgeon’s assistant in the Jacobites’ attempt to depose

the Hanoverian monarchy and return the Stuarts to the British throne. However,

the Battle

of Culloden (April 16, 1746) – a crushing defeat for the Jacobites – was a

disaster for the young doctor, who eventually fled to Pennsylvania

in March 1747 after a year on the run in his native Aberdeenshire, possibly

by means of a ship sailing from Leith to Philadelphia. Ironically, however, his

experience of life in a brutal American frontier war would push him into the

arms of the Hanoverian armies and militias he had once opposed.

ARCHAEOLOGY: The Battle of Culloden

The best book on Culloden is Culloden:

The History and Archaeology of the Last Clan Battle by Glasgow

University’s Dr. Tony

Pollard (writes about the 'last pitched battle on British

soil’ here).

In terms of video, watch Dr. Pollard’s lecture: ’Old Wounds, New Perspectives: The

Archaeological Investigation of Culloden Battlefield’ for a short background

to the Jacobite risings and Culloden, given to Middle Tennessee State University on

September 11, 2013. Dr. Pollard (@DrTonyPollard)

also appears with Dan Snow (@thehistoryguy)

on this BBC film about

the archaeology of the Jacobite Rebellion.

If you are interested in studying conflict archaeology, Love

Archaeology’s alma mater, the

University of Glasgow hosts The

Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, directed by Dr. Pollard and Dr. Iain Banks.

You can visit the Culloden Battlefield, which is curated by the National Trust for Scotland, or learn more about the site at their dedicated website. Glasgow University also has a great page about its archaeology:

5 [Image: Archaeology of Culloden, University of Glasgow]

British Hero: America, War Again,

and Friendship with George Washington

The sources agree that Mercer practiced medicine for

approximately eight years (1747-1755) in a frontier settlement – given by

Goolrick (1906: 23) as Greencastle – in the Conococheague

Valley, western Pennsylvania. This area is to the east of what is now Mercersburg.

A plausible if unproven suggestion is that Mercer lived in

this liminal, border, area to avoid unwelcome recognition as a Scottish rebel

in the more populated east (Siry

2012). Shortly after Mercer left Scotland, George II issued ’An Act for the King’s most Gracious,

General, and Free Pardon’ (also ’Act

of Grace’) to (most) Jacobites, but it appears as if this required the

swearing of fealty to the Hanoverian monarch, so it may not have appealed to

the young exile. In any case, Siry (2012) suggests that Mercer heard of this in

1754 on the outbreak of the French and Indian War and 'he no longer had to fear

arrest’.

If not arrest, Mercer had war to fear: his location ensured

that he could not avoid the French

and Indian War (c.1754-61), which erupted over the disputed borders between

New Britain, New France, and those remaining Native American lands that the

French and British had yet to claim:

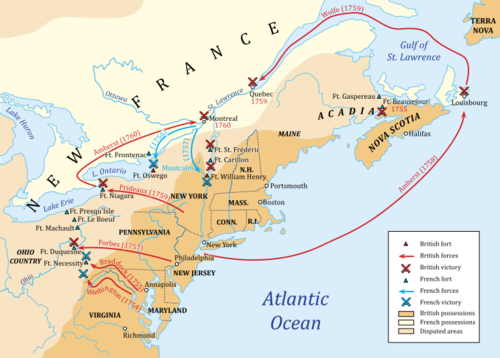

6 [Map: Wikicommons French and Indian War, Wikipedia, by Hoodinski]

Mercer and his Incredibly Confusing

French and Indian War History

Regarding Mercer’s service history in the French and Indian

War, this is the most accurate statement that can be made from my internet

methodology: Hugh Mercer was involved.

All sources agree on this. The actual details, outlined below, have been so

embroiled in legend and the repetition of rumor that George O. Seilhamer,

writing in 1905, wrote:

'It is surprising that

these fictions should have been repeated from their inception in 1824 to the

present time with almost unanimous approval, while no writer ever attempted to

ascertain the truth in regard to Mercer’s services in the French and Indian

War’.

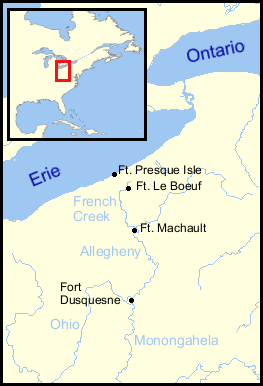

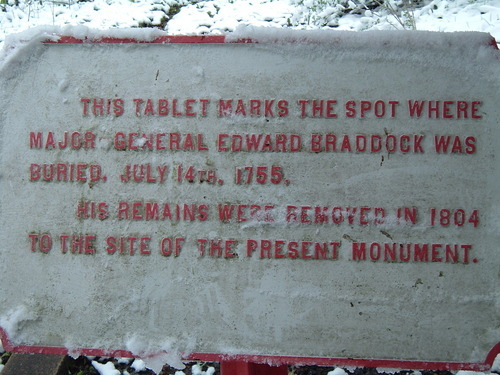

1755, July

Event: General

Edward Braddock’s disastrous military

expedition against Fort Duquesne (modern Pittsburgh) and its French and

Native American defenders ends in Braddock’s death and a bloody rout.

Mercer: Seilhamer

(1905) suggests that, as no-one mentions him in contemporary documents, Mercer

was very likely not involved. Goolrick (1906) claims that Mercer was with

Braddock, was wounded, then had to trek alone back to his own lines. Wikipedia

doesn’t put Mercer with Braddock, but does have him coming to the aid of the

wounded who returned, joining up with British forces as a result of 'the same

butchery he remembered at Culloden’. Young

(2013) offers you your pick of the above, adding the suggestion that Mercer

went to the aid of the survivors at Fort Cumberland, 70 miles west of his home.

1756, March

Event: All agree

that Mercer was made a Captain of the Pennsylvania militia in March 1756.

Mercer: We are

safest when we take the following view from Seilhamer (1905) – ’That Dr. Mercer was active in promoting

measures for the protection of the Conococheague frontier in the autumn of 1755

and the winter of 1755-56 may be assumed, but we have no knowledge of his

movements until March 6, 1756, when he was commissioned a captain in the

service of the province of Pennsylvania. From that time until his removal to

Fredericksburg, Va., after the close of the French and Indian War…the sources

of information concerning him are ample and trustworthy’.

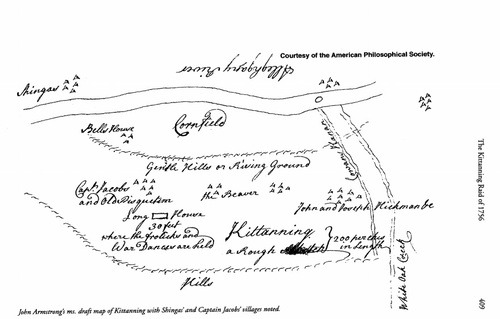

1756, September

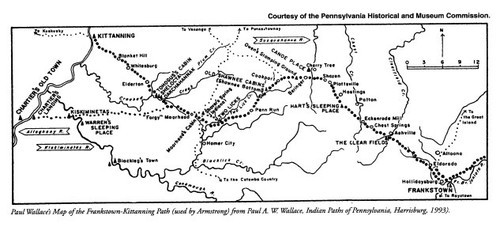

Event: September

8, 1756, saw Lt. Col. John

Armstrong’s infamous

attack on the Native American Delaware village of Kittanning in western

Pennsylvania (40-miles NE of Fort Duquesne), as the colony tried to protect

itself from French forces by means of force projection in the aftermath of the

Braddock disaster. For more on the Kittanning Raid, read James P. Myers’ 1999 article.

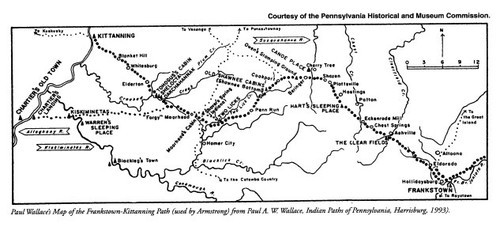

6b [Image: Kittanning Path

Map, Myers 1999]

Mercer: Wikipedia

states that Mercer was wounded at Kittanning before enduring a 100-mile solo

trek back to his own lines. Goolrick (1906) places the trek before Kittanning,

although has Mercer being wounded in Armstrong’s expedition before being given

a silver memorial medal in recognition of his bravery by Philadelphia. Young

(2013) has Mercer being badly wounded, and that this was 'probably’ at

Kittanning. The ever-cynical Seilhamer

(1905) argued that, ’Captain Mercer

participated [at Kittanning] and was

wounded; that he was reported as carried off by his ensign and eleven men, who

left the main body in their return to take another road; and that upon the

return of the expedition to Fort Lyttleton he had not yet arrived’.

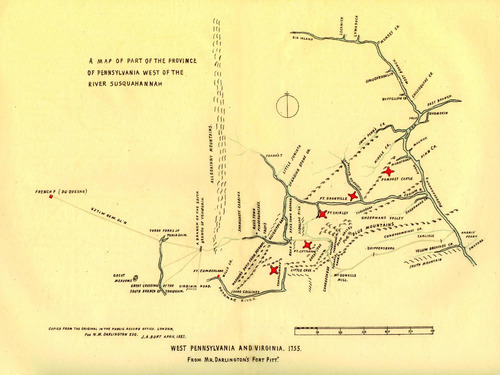

7a [Map: Forts

in Kittanning episode, Libraries PSU]

It seems almost certain that Mercer was involved in the

attack and was shot in the arm or wrist. Myers (1999: 411) talks about

Armstrong’s report of the Kittanning Raid – written on his return to Fort

Lyttleton September 14 – as mentioning that Mercer had been involved in a rear-action

and was reported missing.

Thanks to Brandon C. Downing’s article, ’The Kittanning Destroyed Medal’ (2012), $12

on JSTOR,

the frequent, unreferenced mentions of Mercer receiving a 'silver memorial

medal’ as a result of the Kittanning Raid now make sense: Armstrong and his

troops did receive a medal – the

first given for bravery in British North America – from the Corporation of

the City of Philadelphia. The impression, deliberate or otherwise, given by

most of Mercer’s biographers was that he alone received it for his epic trek

home. Sharp biographical practice aside, we are fortunate that some examples

can be found:

7b [Image: Kittanning

Destroyed Medal, Libraries PSU]

STOP PRESS: How The Internet Led Me to

Hugh and his Kittanning Medal

While finishing off this blog, I discovered an incredible

pdf in OMSA.

I then phoned – across the actual ocean – the wonderful Hugh

Mercer Apothecary Shop, a museum dedicated to his life within the business

Mercer established in Fredericksburg after the French and Indian war. This is

what I found out:

Presented to Mercer by Colonel Armstrong, who had been given

them by Mayor Shute of Philadelphia, Hugh’s medal remained in his family for

nearly 200 years. Then, on January 13, 1953, his great-great grandson, Hugh

Mercer Curtler, donated it to Fredericksburg’s City Council. The OMSA journal

then adds, 'Apparently, the medal was accompanied by a letter written by

Colonel Hugh Mercer in January, 1835, which reads:

'Medal to

Gen Mercer, by the City of Philadelphia

'This highly

valued medal, in memory of my venerated father, was presented to him by the

Corporation of the City of Philadelphia for his bravery and good conduct as

Captain of Infantry in the destruction of Kittanning, an Indian Settlement in

the Colony of Pennsylvania, under Colo Armstrong in Sept 1756, soon after my

father came from Scotland in early life.

’We were

then British Colonies, and those Campaigns (commonly called Braddock’s War in

1755-'56, when Washington too commenced his military career) were between the

Colony of Pennsylvania and the French and Indians – Kittanning was near

Pittsburg, now one of the most flourishing cities in the U. States - the French

had a fort there, called Du Quesne - afterwards Fort Pitt.

’Jan'y 1835

– H. Mercer’.

It was incredibly exciting to phone Genevieve

Bugay, manager of Mercer’s Apothecary, to have it confirmed that they have it

in their museum. Violent in its depiction, it is very much of its time:

7c [Image: Mercer’s

Kittanning Medal, HMAP]

(I know: it’s an awesome piece of history and material culture).

If we have cleared up the mystery of his medal, what

remains uncertain is how Mercer got back from Kittanning, given that he might

have got one just for participating, and not necessarily for an epic solo trek. Armstrong’s contemporary report

listing as Mercer being missing does at least suggest that it may have occurred

(Myer 1999: 411). Here goes:

Dried Clams and Snake Supper:

The Legend of a 100-mile Trek

The story goes that, separated from his men at Kittanning, Mercer

trekked alone for 14 days and 100 miles

before reaching safety. The following is widely reported on the Internet as

being from the Pennsylvania

Gazette dating to September 23

or 30, 1756:

'We hear that Captain

Mercer was 14 Days in getting to Fort Littleton. He had a miraculous Escape,

living ten Days on two dried Clams and a Rattle Snake, with the Assistance of a

few Berries. The Snake kept sweet for several Days, and, coming near Fort

Shirley, he found a Piece of dry Beef, which our People had lost, and on Trial

rejected it, because the Snake was better. His wounded Arm is in a good Way,

tho’ it could be but badly drest, and a Bone broken’.

We know from Myers (1999: 417, n. 2) that there certainly

were reports in the Gazette about

Kittanning on September 23 and 30, but the online

archives are behind a paywall, so I couldn’t check them.

I want to believe: because if the Gazette entry is accurate, but embellished, it shows mythologizing

happening in Mercer’s own lifetime, which would be awesome. (Thanks to M.R. Wood

for this point).

The Forbes Expedition and Revenge at

Fort Duquesne (1758)

Snake-eater or no, it is evident that Mercer impressed his

peers and the wider public in 1756/7, being promoted to the rank of Major on

December 4, 1757 (See Pennsylvania Archives,

Bell

1997: 449) and put in command of all Pennsylvania troops west of

Susquehanna (Goolrick 1906: 28; Bell 1997: 449).

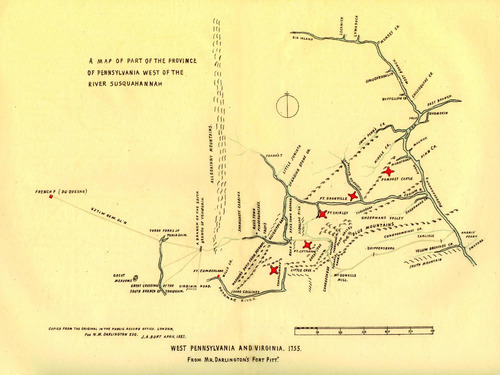

1758 saw the tide turn for the British as William

Pitt (the Elder) became Secretary of State in the Newcastle/Pitt

Ministry (c.1757-1762) and more resources were sent to fight the French and

their allies (Siry 2012). This strategy can be seen in the Forbes

Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne (this being the third British attempt)

at the Forks of the Ohio River.

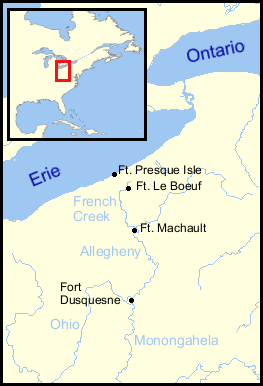

7d [Image: Fort Duquesne, Wiki: “French

Forts 1754” by Thomas Cool]

Brigadier-General John

Forbes was another of those Scottish doctors-turned-soldier in America –

they seem to be everywhere, as this 2009 book

by Roger L. Emerson demonstrates – but his own health ensured that effective

leadership of the expedition fell to Henry Bouquet. George

Washington, hero

of Braddock’s disaster, commanded a contingent of Virginians.

The main body of 6,000 men – 2,000 mainly Highland Scottish

Regulars with the remainder militias from Virginia and Pennsylvania – advanced

excruciatingly slowly toward Fort Duquesne along the road they had to build

through the wilderness (Washington bitterly disagreed with this, preferring to

follow the route he took with Braddock in 1755). By mid-September, the British

were close enough to send out the Highlanders for a reconnaissance mission, but

it was crushed

when it tried to storm the fort itself, with Wikipedia reporting that the

Scots’ heads and kilts were displayed on Duquesne’s walls.

Another disaster involved Mercer and Washington. On November

12, Forbes sent both men to ward off a French night sally/sortie, but their

split forces ended up firing on each other in the darkness. 35 men died, but

the French raid was their last hurrah: with a 10th of the men and

low on supplies, the French burnt Fort Duquesne on the night of November 24,

1758, and fled; the British entered the next day.

Mercer’s

good work here over the following months would build both a firm basis for the

future Pittsburgh, but also for his later career in the Revolutionary Continental

Army.

How Hugh Helped Build Pittsburgh

Mercer was entrusted to build the temporary precursor to Fort

Pitt, known in contemporary maps as 'Mercer’s Fort’, in what would become

Pittsburgh. This stabilized British control over the Ohio Country, disputes

over which had sparked off the French and Indian War. Concerning Mercer’s

capabilities for such an important role, Jeffrey

Amherst, overall British commander in North America, wrote to Bouquet: 'I am very sensible of his zeal and

attachment to the King’s Service and his judgment and alacrity in executing

whatever may tend to the honor of his Majesty’s Arms’ (Siry 2012; after

Waterman 1941: 56).

8 [Image: Fort Duquesne, Pittsburgh, Dr. Jen Novotny]

In charge of 200 men, Mercer’s eight-months’ work at the

fort – which he apparently

described as 'huddled up in a very hasty manner’ – involved 'building a saw

mill’ and 'trying to make tar’, along with planting vegetable gardens, offering

medical advice, and preparing for the expected French counter attacks (Bell

1997: 449). Life at Fort Mercer was nothing if not varied.

Fun Facts: a Fort

Mercer – named after Hugh’s

construction – features in the 2010 Rockstar video game Red Dead Redemption

(see below). The name Fort Mercer also reappeared in the Revolutionary War in

the guise of a 1777 fortification

on the Delaware River, named in his honor.

8a [Image: Red Dead Redemption’s 'Fort

Mercer’, RedDead.Wikia]

Promoted to Colonel on April 23, 1759 – the year in which

Britain turned the tide in this global war – Mercer revealed a comic side

when it was proposed to send some of his garrison home for recuperation:

'My Opinion as to

their going to the Settlement you shall have all the freedom in life: I never

knew any other Advantage accruing to Soldiers, I mean ours, from being in Towns

on the frontier, than black eyes, Claps, & eternal flogging; and unless

Carlisle & Shippensbg are of late miraculously altered in point of Morals,

the old game at either of those seats of Virtue and good manners would

undoubtedly be play’d over; especially as it is intended the men should receive

their Pay there, to enable them, more & more, besides having their pockets

pick’d by Tavern keepers’ (Bell 1997: 449, Shippen Papers IV, 39 (HSP)).

That’s fairly top-end lolz for 1759, and it worked: his soldiers

stay’d put (Bell 1997: 449, + refs.).

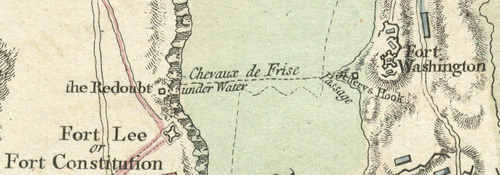

ARCHAEOLOGY: The French and Indian War

There are some truly superb pieces of material culture

associated with the war in this online chapter

of 'The Backcountry War’, from ’Clash of

Empires: The British, French, and Indian War, 1754-1763’, including

Mercer’s Kittanning medal featured above.

Braddock Expedition:

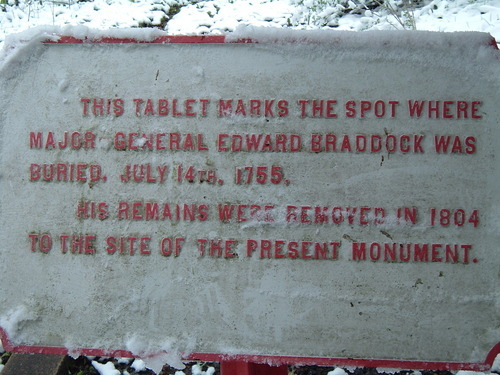

The National Park Service has more on General Braddock's Road and his Grave (including the initial, hasty, pit dug on the orders of George Washington, who then got the fleeing British soldiers to trample over it so that the French wouldn’t notice the disturbed earth and dig it up).

9 [Images: Braddock’s Original Grave, Dr. Jen Novotny]

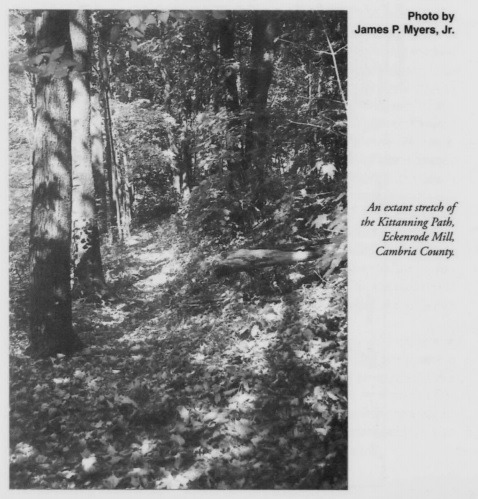

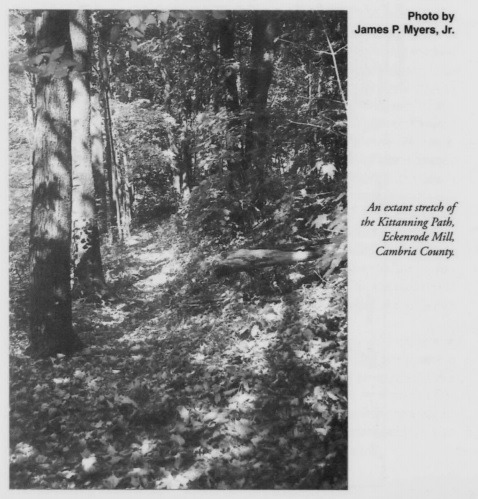

Kittanning Raid: Beyond

the 'Kittanning Destroyed Medal’ seen above, parts of the Frankstown-Kittanning

Path used by Armstrong and Mercer can still be found (Myers 1999: 406)

10 [Images: Kittanning Path archaeology, Myers 1999: 406]

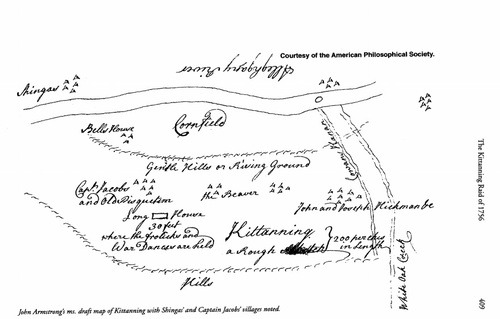

In terms of material culture, Armstrong’s very, very cool hand-drawn map of

Ki style=“text-align: center;"ttanning survives (Myers 1999: 409).

11 [Images: Armstrong’s hand-drawn

map, Myers 1999 + acknowledgements]

Fort Pitt: The

'lower remnants’ of the rampart walls built when Mercer was in command (under

General John Stanwix) have been excavated:

12 [Images: Fort Pitt Trench 3, Dr. Jen Novotny]

More generally, recent work has been done on The Archaeology of French and Indian

War Frontier Forts (Babits & Gundulla 2013), like at Fort Edwards, West Virginia.

The French and Indian War:

Sparkplug of Global Conflict and American Revolution

The French and Indian War was a key event in the countdown

to the American Revolution. As the US

Department of State notes: 'The war provided Great Britain enormous

territorial gains in North America, but disputes over subsequent frontier

policy and paying the war’s expenses led to colonial discontent, and ultimately

to the American revolution’.

Washington’s War?

See here

for more on George Washington’s critical involvement in the earliest actions of

the French and Indian War in the 1754 engagements at Jumonville Glen

and Fort

Necessity.

When Hugh met George (Washington)…

…is something that no-one on the Internet knows. Given the

lack of information over Mercer’s whereabouts in the period 1755 to March 1756,

it is difficult to say. Here, Goolrick (1906: 28-9) notes:

’Whether Hugh Mercer [first] met George Washington at Braddock’s defeat [1755], or at the headquarters of the Forbes

expedition against Fort Duquesne [1758],

there seems to be some conflict of opinion and statement among his biographers.

The time and place of that meeting is of no very material moment. One thing

seems to be absolutely certain, that they did meet, and an attachment sprang up

between them which lasted as long as Mercer lived. And, further, that as a

result of that meeting and that attachment, on the advice and at the suggestion

of Washington, Virginia became the home of Hugh Mercer, and the State of

Pennsylvania lost him as a citizen’.

Years later, during the Revolution, Washington also seems to

have supported Mercer’s advancement within the Continental Army (Goolrick 1906:

31; Embrey 1937: 121). This was after a long friendship forged in

Fredericksburg, Virginia, where Mercer moved in 1761.

General Practice in Virginia, 1761-1775:

Medicine, Masons, and Ferry Farm

Mercer was discharged on January 15, 1761, which reflected

the ending of effective French offensive capacity throughout North America and

the demobilization (or transfer to other Seven Years’ War theatres) of many

soldiers. Having befriended many Virginians, Mercer followed Washington to

Virginia.

On February 12 (Bell 1997: 449-450), he wrote to Henry

Bouquet, his CO on the Forbes Expedition:

'…all Prospect from

the Pensylva Service failing, I determin’d upon applying myself to the Practise

of Physick, and this Place was recommended as likely to afford a genteel

subsistance in that Way. Whether it will answer my expectation, I cannot yet

judge; but from the reception I met with the Gentlemen from here, have reason

to imagine it worthy a few months’

trial’.

The yearning he felt for military service did not

immediately wane. Hearing that a permanent army might be raised, Mercer took a

break from the medical practice and apothecary business he was establishing to

write Bouquet again (Bell 1997: 450, from Papers

of Henry Bouquet).

’I might again appear

in a Military Capacity; For I must own I would prefer something genteel in that

Way, to the drudgery of Business. Is there any likelihood of such a Measure

taking Place?’.

Unfortunately for Mercer, there wasn’t, and he would remain

in Fredericksburg until 1775. In his work, he was successful, treating George

Washington’s younger brother Charles, his mother Mary (see below), and his

step-daughter Patsy Custis. This information can be found in Bell (1997: 450),

who had access to Mercer’s account book covering the period 1771-5. Mercer had

literally hundreds (some 300+) of families on his books in the early 1770s,

entered into medical partnerships with fellow doctors, and had some of his

correspondence on medical matters to John Morgan

– who, like Benjamin Rush, had studied medicine in Edinburgh – read to the

American Philosophical Society.

Outside of work, Mercer joined the still

extant Masonic Lodge, No. 4, alongside George Washington and – amazingly –

as many as five other future generals of the American Revolution. The Lodge lists them as Washington, Mercer, George Weedon, William Woodford, Fielding Lewis, Thomas Posey, and Gustavus

Wallace. See here

for MountVernon.org’s article on Washington, Mercer, and Freemasonry.

Mercer was also involved in St. George’s Episcopal Church,

and managed a 'lottery to raise £450 for a new church and organ’ (Bell 1997:

450, from the Virginia Gazette, July

14, 1768). At an unknown date, Mercer married

George Weedon’s sister-in-law, Isabella Gordon, daughter of John, the local

tavern-owner (Goolrick 1906: 105-6; Bell 1997: 450). They would have five

children, and Mercer may have been trying to secure their inheritance when he

maintained his claim to western land grants given as a reward for military

service in the French and Indian War (Bell 1997: 450, + Mercer 1773

correspondence refs.).

While practicing medicine in the midst of what was a

very Scottish community in which Scots-born 'Father of the US Navy’ John

Paul Jones lived for a time, Mercer purchased Ferry Farm – George

Washington’s boyhood home – where a famous cherry tree

may (or may not) have once stood. In paying £2000 for this property in 1774, Mercer proved that

his business interests – beyond medicine, he also owned a ferry service – were

profitable, and he felt confident (Goolrick 1906: 38; Bell 1997: 451 + refs).

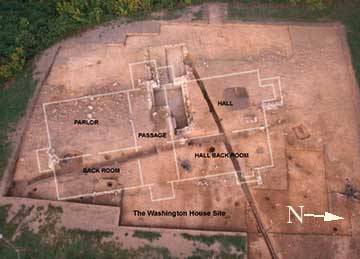

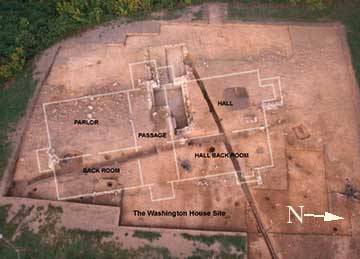

ARCHAEOLOGY: Ferry Farm

Facing Fredericksburg on the opposite bank of the

Rappahannock River, George would have called Ferry Farm home from 1738 until he

inherited Mount Vernon in 1754. As with Washington’s Mount Vernon estate (see here

and/or below), there is a lot of cool archaeological work being done with Ferry

Farm, like the field

school and 3D-scanning

project.

We now know that the house inhabited by the Washingtons was

a wooden structure covered in clapboards, with chimneys at either end of its

1.5 storeys. Evidence of the small Christmas Eve fire of 1740 – burnt charcoal

and plaster – was also discovered, as were the kitchens and slave quarters.

Thousands of C18th artifacts were unearthed, including this pipe with Masonic

stamp:

13 [Image: Ferry Farm Masonic pipe, GWF]

Read more about the archaeology

of Ferry Farm on the George Washington Foundation (GWF) website. MountVernon.org have a page

of their digital encyclopedia devoted to the farm. Please note that the GWF

are holding Archaeology Day on February 16, 2015.

14 [Image: Ferry Farm excavations, GWF]

When Good Neighbors Become Good Friends:

Mercer and the Washington Family

14b [Image: Mary

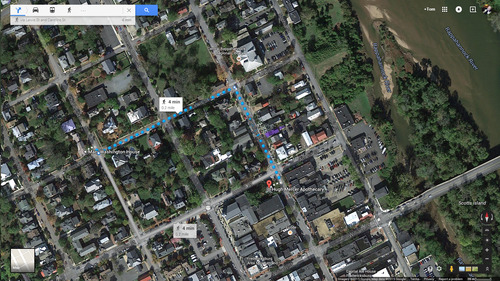

Washington journey to Mercer’s Apothecary, Google]

As a physician, Mercer had regular contact with Washington’s

mother, Mary. Embrey (1937: 122) notes that Mercer’s account book, which had been

at the Clerk’s Office in Fredericksburg for many years, contained several

entries pertaining to 'Madam Washington’. One source

claims that Mercer treated Mary for the pain of the breast cancer by giving her

a 'mild opiate’ on a daily basis. We have a

letter from another Fredericksburg medic, Elisha Hall, to his cousin (Benjamin

Rush) asking for advice on Mary’s treatment. Some other sources for Mary, who

lived around the corner from Mercer’s apothecary (see above) in a house

which still stands, have been collated by Paula S. Felder here,

and there is a fascinating website devoted to

her life.

15 [Image: Mary

Washington House, Preservation Virginia]

Embrey (1937: 124) also tells us that George Washington

managed his and Mary’s landholdings on the Rappahannock River from a desk he

maintained in Mercer’s apothecary. Visits seemed to have been reciprocal, and

Goolrick (1906: 32) adds that Mercer 'occasionally paid a visit to the future

"Father of the Country” at Mount Vernon’, an estate and house that still

exists:

ARCHAEOLOGY: Mount Vernon, Va.

Mount Vernon has a superb website, and has much on Washington’s

involvement in actions in which we know that Mercer

was involved. The website also has a world-class archaeology

section – which doesn’t shy away from the archaeology

of slavery – that you could easily lose hours navigating.

16 [Image: Washington's trunk plate, Mount Vernon]

The above image – of a copper trunk plate inscribed 'Gen:

Washington’ – is from Mount Vernon’s South

Grove Midden excavations. The midden was the main repository for the

Washington family’s domestic trash in the decades prior to the Revolution (esp

c.1735-1765). There is a dedicated midden

website containing object biographies of the trunk plate,

and a 2013 Popular Archaeology article.

Fun Fact: Washington’s

next-door neighbor for a period was Scot George Buchanan (d. 1762), a

Glaswegian merchant who named his Glaswegian property 'Mount

Vernon’ due to the fact that his Virginian estate bordered that of the

Washington family. The area retains the name to this day.

What was Hugh Mercer actually like?

I have found two sources – Goolrick (1906: 31) and Embrey

(1937: 121) – who quote Englishman Dr. J.F.D. Smythe’s 1784 recollection of

visiting Mercer before the war broke out:

'I arrived in Fredericksburg and put up

at an inn kept by one [George] Weedon, who is now a general officer in the American Army, and who was then very

active and zealous in blowing the flames of sedition. In Fredericksburg, I

called upon a worthy and intimate friend, Dr. Hugh Mercer, a physician of great

eminence and merit, and, as a man, possessed of almost every virtue and

accomplishment. Dr. Mercer was afterwards Brigadier-General in the American

Army, to accept of which appointment I have reason to believe he was greatly

influenced by General Washington, with whom he had been long in intimacy and

bonds of friendship. For Dr. Mercer was generally of a just and moderate way of

thinking and possessed of liberal sentiments and a generosity of principle very

uncommon among those with whom he embarked’.

It is a picture of a pleasant person, and one which

corroborates evidence for his relaxed nature and sense of humor notable in the correspondence from his period in charge of Mercer’s Fort, as quoted above.

Archaeology: Dr. Mercer in Fredericksburg (1761-1775)

Wonderfully, a quick Google – other Internet search engines

are available – will find you Washington Heritage Museums’ preserved

doctor’s surgery, where Dr. Mercer practiced medicine in his c. 1771/2 apothecary:

17 [Image: Apothecary exterior, Preservation

Virginia]

In terms of material culture, the Hugh Mercer Apothecary

Shop contains Mercer’s 'Kittanning Destroyed’ medal, described above. Discussing

the (1920s) restoration of the apothecary by the Citizen’s Guild of Fredericksburg,

Embrey (1937: 122) notes that 'the shelves and drawers were found intact, the

fronts of some of the drawers bearing labels in Dr. Mercer’s own handwriting’.

Embrey includes a letter written by the restoration architect,

Edward W. Donn, Jr. (dated August 20, 1928), in which he describes his standing

building survey and its archaeology:

’The excavations about

the site brought to light some relics of old bottles , very much oxidized, an

old drilling foil and several other articles...’.

Revolution! American Patriot: Gunpowder and Plot

Mercer’s loyalty to the British Army – and it could be

argued that it was only born out of necessity in the French and Indian War and

a love of adventure – proved a one-off: In 1775, he joined Fredericksburg groups

that shared military intelligence with their fellow Revolutionaries, being part

of an assembly that wrote to Washington, alarmed at the news that Scot Lord

Dunmore (see below), the very-soon-to-be-last Royal Governor of Virginia, had,

at night on April 20/1 begun removing the gunpowder

from the Williamsburg Magazine. Bell (1997: 451) has Mercer offering to lead

men to Williamsburg.

18 [Image: Williamsburg

Magazine, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation]

Goolrick (1906: 33) quotes a letter dated April 25 – saying

that it was written by Mercer, although it may have been a group effort – which

explains why they did not march on Williamsburg:

’We are not sufficiently supplied with powder ; it may be proper to

request of the gentlemen who join us from Fairfax and Prince William to come

provided with an over-proportion of that article’.

On April 30, Goolrick (1906: 34) reports that Alexander

Spotswood confirmed to Washington the decision of the Fredericksburg militia to

stay:

’I am extremely glad to inform you

that after a long debate it was agreed that we should not march to

Williamsburg’.

You can learn more details about the incident here. This practice

of emptying magazines in areas of dubious loyalty to the British Crown had led to

Battles

of Lexington and Concord, where the first firefights of the Revolution

occurred on April 19, i.e., the day before Williamsburg’s 'Gunpowder Incident’

[See the 'shot

heard around the world’].

ARCHAEOLOGY: Colonial Williamsburg

If you can’t visit Colonial Williamsburg, you can still visit

its amazing website. Beyond the wonderful

podcasts and videos, not to

mention educational

materials, it has pages devoted to

archaeology, where

to find it on site, and a kids’

archaeological page to boot. The CW Foundation looks at colonial

archaeology and material culture, involving urbanization, community development,

zooarchaeological method, GIS, and archaeobotanical research. Annual field-schools

are undertaken with the College of William and Mary.

19 [Image: Colonial Williamsburg,

CWF]

Rivalry! 1775, Patrick Henry, and the Lack of Trust in Scots-American Loyalists

In August, 1775, Wikipedia notes that Mercer was prevented

from leading the Virginian regiments – there were three of 1,000 men each –

because he was a 'Northern Briton’. Here, Goolrick (1906: 39-41) expands: It

had been decided that the commander of the 1st Regiment would be the

commander-in-chief. When it came to the vote, Patrick Henry of

'Give me Liberty, or give me Death!’ fame was elected over Mercer, despite the

fact that only the latter had (extensive) military experience (Selby 2007: 50).

Goolrick (1906: 40) suggests that there were some doubts over Mercer’s American

loyalties as he had not been born in the colonies (to be fair, Lord Dunmore was

a case in point). It should be pointed out here, however, that, like Mercer,

Henry’s father was from Aberdeenshire in Scotland.

Here, John E. Selby (2007: 50) adds the important note that

many Revolutionaries were suspicious about Scots as many Scottish-born

colonists were Loyalists. Articles in Wikipedia about Loyalists,

Loyalists

Fighting in the American Revolution, Toryism, and United Empire

Loyalists provide more background, and Arthur Herman’s 'How

the Scots Invented the Modern World’ contrasts the popularity of Loyalism

amongst Scottish-born Americans with strong Patriotism amongst the Scots-Irish.

In any case, Washington was aghast at the thought of Henry’s

lack of military experience: Selby

(2007: 50) quotes his response – ’I think

my countrymen made a capital mistake, when they took Henry out of the senate to

place him in the field; and pity it is, that he does not see this, and remove

any difficulty by a voluntary resignation’. The negative reaction to

Henry’s appointment led to Mercer removing himself from the election for the

colonelcy of the 2nd Regiment (Selby 2007: 50; cf. Thomas

1837: 572-3).

In any case, Mercer was elected as Colonel to the Minute Men – so called

because, in theory, they could be ready for battle within 60 seconds – of four

Virginian counties. Goolrick (1906: 33) quotes the order:

’Election of officers

of minutemen and regulars for Caroline, Spotsylvania, King George and Stafford

counties, Virginia, September 12, 1775. At a meeting of the select committee

for the district of this county, the counties of Caroline, Stafford, King

George and Spotsylvania, the following officers were elected: Minutemen Hugh

Mercer, Colonel…’.

Promotion: Colonelcy of 3rd Virginia Regiment, January 10, 1776

On January 10, 1776, Mercer was appointed the first

commander of the 3rd Virginia Regiment (Bell 1997: 451), which the

Virginia Convention had previously decided not to fund (Selby 2007: 51),

presumably after the fiasco of the elections of the leaderships of the 1st

and 2nd Regiments. Goolrick (1906: 39) quotes Mercer as having

offered his service to the Virginia Convention with the promise that he would ’serve his adopted country and the cause of

Liberty in any rank or station to which he may be assigned’. Goolrick

(1906: 41) also includes the minutes from the Virginia Convention:

’Wednesday, January

10, 1776, Convention proceeded by ballot to the appointment of a Colonel of the

Third Regiment, and there was a majority of the whole Convention in favor of

Hugh Mercer. Resolved, therefore, that the said Hugh Mercer be appointed

Colonel of the Third Regiment’.

Spotsylvania county’s Committee

of Safety – described by Wikipedia as a type of 'shadow government’ set up

by the Americans (and normally in control of the militias) – responded to

Mercer’s promotion with the following statement, as recorded by Goolrick (1906:

41-2):

’The committee of the

county, to express their approbation of the appointment of Col. Mercer, and to

pay a tribute justly due to the noble and patriotic conduct which that

gentleman has uniformly pursued since the commencement of our disputes with the

Mother Country, which was so strikingly displayed on that occasion, entered

into the following resolve: Resolved, That the thanks of this committee be

presented to Colonel Hugh Mercer, Commander-in-Chief of the Battalion of Minute

Men in the District of this County, and the counties of Caroline, Stafford, and

King George ; expressing the high sense of the importance of his appointment to

that station, and our acknowledgements of his public spirit in sacrificing his

private interest to the service of his Country. ALEXANDER DICK, Clerk.’

This website

lists his service with the 3rd Regiment as being from February 12,

1776, to June 5, 1776.

Mutiny!

Mercer’s first job on taking command of the 3rd

Regiment was to deal with the mutinous behavior of a group of soldiers amidst the

generally chaotic background of the resignation of Henry due to the removal of

overall command from his position as Colonel of the 1st Regiment

(Selby 2007: 88-9).

Whereas Goolrick (1906: 44-5) suggests that Mercer quelled

the mutiny with a firm, but calm, reprimand, Selby (2007: 89) – whose account

is well-footnoted

with Virginia Gazette references

(2007: 350) – suggests that Mercer’s rebuke was met with the mutineers’ threat

of calling a court of enquiry, and that Mercer 'had to apologize publically to

the company. He meant nothing personal, he assured them’. This disparity –

compare Goolrick (1906: 44-5) with Selby (2007: 89, 350) – drives home the

point that Goolrick, being a cheerleader for Mercer, can ignore facts that

challenge his hero narrative.

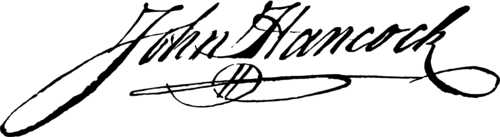

Promotion Again: JOHN HANCOCK and General Mercer, June 5, 1776

Mercer was appointed to the Continental Army as a Brigadier-General

by the Continental Congress on June 5, 1776. The order (Goolrick 1906: 46) from George Washington was

sent by John

Hancock:

'President of Congress

to General Mercer, Philadelphia, June 6, 1776. Sir: I am directed by Congress

to inform you that they yesterday appointed you a Brigadier-General in the

armies of the United Colonies, and that they request you will immediately on

receipt hereof set out for headquarters at New York; for which purpose I am

commanded to forward you this by express. Should you take Philadelphia in your

way, I must beg you will do me the favor to call at my house, as it is highly

probable I shall have something in charge from Congress ready for you at that

time.

I do myself the pleasure

to enclose your commission; and have the honor to be, sir,

Your most obedient and

very humble servant,

Goolrick (1906: 46-7) includes Mercer’s reply (note the

reference to our old friend, Lord Dunmore) -

'Williamsburg, June

15, 1776.

Sir: I had the honor

yesterday to receive your letter of the 6th inst., together with a commission,

appointing me a Brigadier-General in the army of the United Colonies. Give me

leave, sir, to request of you to present to the honorable Congress my most

grateful acknowledgements in this distinguished mark of their respect.

I was on duty with

part of my regiment before Gwinns Island, where Lord Dunmore has taken

possession, when your instructions reached me; in consequence of this I shall

use my utmost diligence, after settling the accounts of my regiment, to wait on

you in Philadelphia, I have the honor to be, sir,

Your most obedient,

humble servant,

HUGH MERCER’.

Lord Dunmore and Hugh Mercer:

From Culloden Allies to Virginia Foes

21 [Image: Lord Dunmore, CWF & Va.

Historical Society]

Remarkably, John Murray (Lord Dunmore)

– whom we met above trying to empty the Williamsburg Magazine the year before –

had, at the age of 15, accompanied his father on campaign with Bonnie Prince

Charlie, serving as Charlie’s page boy. Imprisoned after the Battle of Culloden

(his father was sent to the Tower of London), Dunmore received a partial pardon

in 1650 and joined the British Army. Like Mercer, Dunmore moved to America,

settling at first in Virginia, before eventually becoming Royal Governor on

September 25, 1771.

Quite the coincidence, then, that Dunmore’s base on Gwynn’s

Island was besieged by his former ally. In July, 1776, the month after Mercer’s

letter, Dunmore was dislodged from the island by General Andrew

Lewis, never to return. He was the last Royal Governor of Virginia.

'Times That Try Souls’: Crisis of the Revolution, 1776

For the American’s ill-fated New York

and New Jersey Campaign, Washington appointed Mercer commander of the 'Flying

Camp/Army’ in July, 1776. This unit was a strategic reserve designed to protect

New Jersey while Washington’s Continentals defended New York (Kwasny 1998: 57).

More details on Mercer’s movements and interactions

with Washington can be found in Google Books in Mark V. Kwasny’s ’Washington’s

Partisan War, 1775-1783’. Kwasny (1998: 63) informs us that Mercer convinced (the already naturally aggressive)

Washington to look to take the initiative against the Regulars whenever

possible, although this was problematic during a period when the Americans were

on the back foot. That said, we do know that Mercer led a diversionary raid

against Staten Island on October 15 with c.600 militia and Continentals,

capturing 20 prisoners in the action (Kwasny 1998: 81-2).

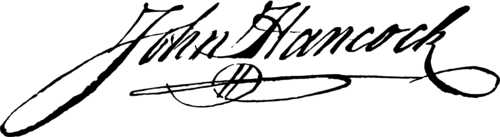

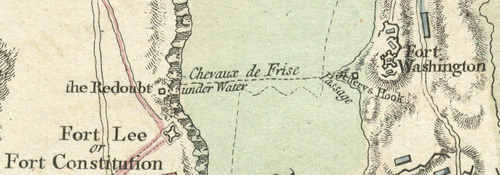

Mercer and the Rise and Fall of Fort Lee, NJ

22 [Image: Hudson, Forts Washington and Lee, Library of Congress]

Mercer’s troops constructed Fort Lee, New Jersey, on the

opposite bank of the Hudson River to Washington’s Fort Washington in a bid to

deny passage to the Royal Navy. We can only assume that Washington remembered

his friend’s success with Fort Mercer in the French and Indian War. Fort Lee - read more about its inauspicious name here - was ill-starred and short-lived, however: in a disastrous period for the

Americans, which had seen the Regulars take New York City in September, Fort

Washington fell on November 16, 1776, in the aftermath of the American defeat

at the Battle of

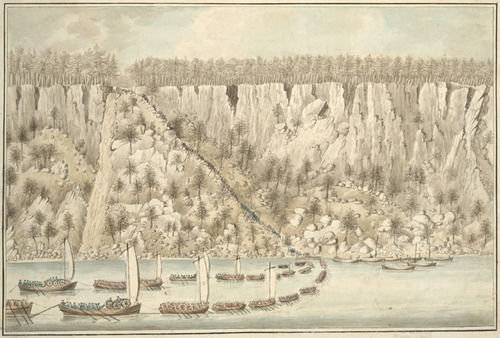

White Plains on October 28. Four days after the fall

of Fort Washington, the (now abandoned) Fort Lee was taken by the British:

23a [Image: Battle

of Fort Washington, by Oneam]

It was at this critical juncture that Thomas Paine, on the

retreat with Mercer and Washington, began his 'American Crisis’

series, the first of which opens with the line:

’These are the times

that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this

crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now,

deserves the love and thanks of man and woman’.

23b [Image: Regulars scale The Palisades toward Fort Lee, NY Pub. Lib.]

The Icy Delaware River: Washington and Mercer, December 25/6, 1776

24 [Image: Washington crossing the

Delaware, Met

Museum]

However you look at it, Mercer was connected in time and

often place to many of the great figures of the American Revolution. Most

importantly, however, Mercer was particularly close to Washington, being actively

involved in the plan

to cross the icy Delaware River – perhaps making the original suggestion – in

order to surprise isolated Hessian soldiers

(British mercenaries) at Trenton, New Jersey (where battles were fought on December 26 and January 2,

1777). The idea that Mercer came up with the Delaware plan is stated in

Goolrick (1906: 49) as being reported by Mercer’s aide-de-camp.

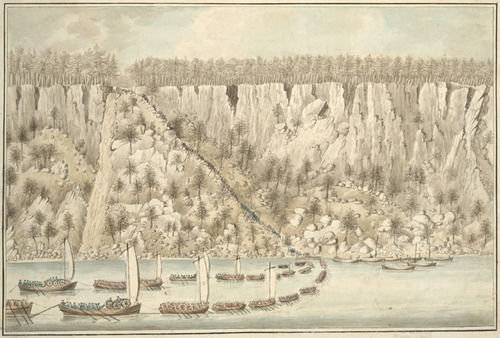

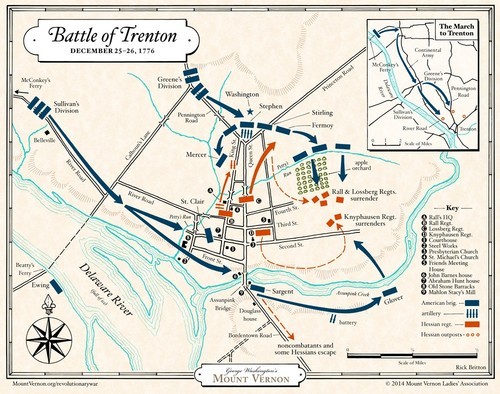

25 [Map: First

Battle of Trenton, Mount Vernon]

Whoever had the idea, the surprise amphibious attack on

Trenton was a total success, at least temporarily turning the tide of the war

in the Americans’ favor. A fully-referenced account of this battle can be found

here

at MountVernon.org.

Damn Rebel! The Battle of Princeton,

January 3, 1777

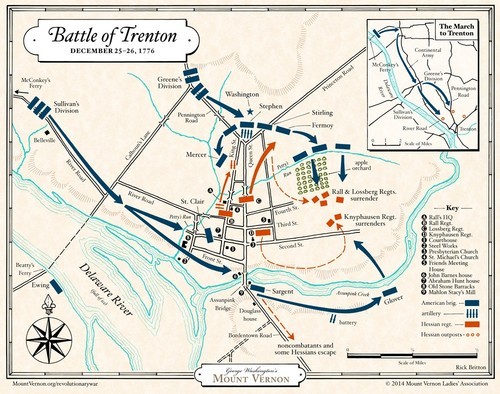

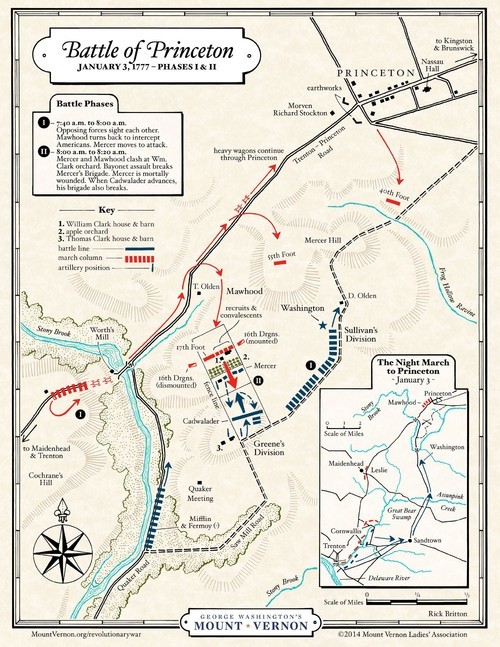

26a [Map: Battle of Princeton, MountVernon.org]

On January 3, the day after the second Trenton battle (also

known as Assunpink

Creek), Mercer led one of Washington’s wings on the approach to Princeton

in a bold attempt to capture the town and threaten the rear of Lt. General Charles

Cornwallis’ army.

Read more here

about the importance of American military intelligence in the lead-up to the Battle

of Princeton, and in particular the wonderful 'Spy

Map’ researched by militia Colonel John Cadwalader and given to Washington

on New Year’s Eve. This amazingly detailed map gave the Americans a highly

accurate bird’s-eye-view of the area and a huge tactical advantage on the day:

26b [Map:

Cadwalader’s Plan of Princeton, Dec. 31, 1776, Library of Congress]

As with the Crossing of the Delaware, it seems that there

was some scholarly

debate in the past as to whether Mercer suggested this daring plan, but I

am no wiser to modern views on this. In any case, Kwasny (1998: 103-4) adds the

detail that Mercer commanded c.350 veteran troops with the task of taking

control of the main bridge to the south of Princeton.

As Mercer’s detachment entered the Clarke Farm orchard on

Princeton’s southern outskirts, Mercer’s vanguard encountered 276 Regulars –

whose numbers included Mercer’s fellow Scot,

Captain William Leslie – commanded by Lt. Colonel Charles Mawhood. Where

Leslie was killed instantly by a musket ball through the heart, Mercer was

fated for worse: his horse shot from under him and separated from his troops,

the Regulars – who thought he was Washington – demanded his surrender with the

words:

'Surrender, you damn rebel!’

Refusing, and advancing with his saber drawn, Mercer was

clubbed and bayoneted, being left for dead with seven bayonet wounds.

One legend has it that Mercer refused to be taken

immediately from the fray, and asked to be propped up against what would become

known as the Mercer Oak,

but this is likely

untrue, although the tree was there at the battle and only died in 2000

(with scions and a sapling grown from one of the original tree’s acorns now at

the site). What is certain is that

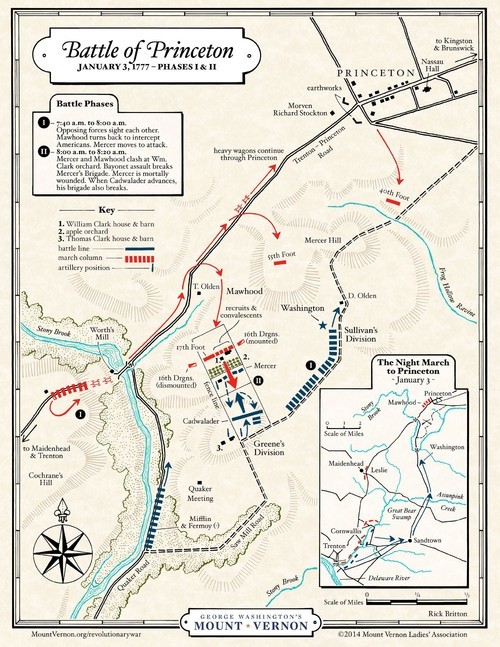

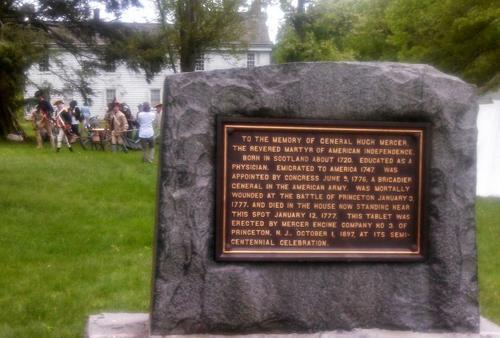

Mercer was taken with the wounded of both sides to the Thomas

Clarke House (see below) at the eastern end of the battlefield, where he

died 9 days later on January 12, despite the efforts of Dr. Benjamin Rush.

The

Americans won at Princeton, but losing Mercer and other important men was,

nevertheless, a major blow.

27a [Image: Memorial to Hugh Mercer

with Thomas Clarke House, Roy Edwards]

Pro Patria Mori? Dr. Rush and the Deaths of General Mercer and Captain Leslie

In the aftermath of Mercer’s horrific death, his

corpse was put on public display in Philadelphia 'where it was exhibited as

evidence of British savagery’ (Bell 1997: 451, as witnessed by Jacob Mordecai).

American anger was also stoked by witness accounts like that

of Dr. Jonathan

Potts, who reported in a letter dated January 5 that the Regulars robbed

the mortally wounded Mercer, 'even to taking the cravat from his neck,

insulting him all the time’ (Bell 1997: 451, letter in Continental Congress Papers).

27b [Image: Death of General Mercer,

Yale

Art Gallery]

In the final coincidences of what was, if I may be allowed

to say, a particularly Scottish battle, Potts had studied for his M.D. in

Edinburgh with Rush,

the Founding Father who, while in Scotland (1766-8), had befriended the

aforementioned William Leslie, the Scottish Captain being painted at the moment

of death by Trumbull on the right of The

Death of General Mercer. In this painting, Rush is advancing towards the

stricken Mercer while Leslie falls; in the middle, Washington rides in on his

horse (all being a-chronological, of course: Washington arrived later after

rallying the troops who had turned back).

Touchingly,

Rush would ensure that Leslie got a fine burial: this blog and Wikipedia entry (both footnoted) describe how the 26-year-old Scot’s body was recovered from

the battlefield. Originally put on a British wagon, the wagon was in turn

captured by the Americans. While treating Mercer and others in the Thomas

Clarke House, Rush – who may have previously given Leslie a letter asking any American captors to parole him to Rush’s house in Philadelphia – heard

of the discovery, and asked Washington to bury Leslie at an appropriate spot on

the Americans’ subsequent march to Morristown. Thus, in the village of

Pluckemin, NJ, a young British soldier was buried with full honors in a funeral

attended by Rush and Generals Thomas Miffin, John Sullivan Henry Knox, and

George Washington. Rush paid for a headstone after the war and, although the

original was replaced, the grave marker still bears the legend:

In Memory of the Hon.ble Capt.n WILL.M LESLIE, Of the 17th British Regiment, Son of the Earl of Leven in Scotland. He fell Jan.y 3.d 1777 Aged 26 Years at the battle of Princeton. His friend Benj.n Rush M.D. of Philadelphia hath caused this Stone to be erected as a mark of his esteem for his WORTH and of his respect for his noble family

A worthy digression, but we end, though, with Hugh Mercer.

Rush recalled years later that Mercer had said to him two days prior to the

Battle of Princeton that he ’would never

submit to lose my liberty. Sooner than bow my neck to the Yoke, I will cross

the mountains, & incorporate myself with the Indians. I will live & die

a freeman’. In a sad addendum, Bell (1997: 451, n. 19) notes that Rush

wrote this recollection on the back of a letter dated April 25, 1803, sent to

him from Hugh’s son, Hugh Jr.

After Trumbull’s paintings, another idealized version of

Mercer’s death is depicted (below) on the Princeton Battle Monument (1922), which is, in its drama, nevertheless a

fitting memorial to this forgotten hero of Scotland and of a United States he

did not live to see:

28 [Image: Battle of Princeton Monument, Kara Kozikowski]

Archaeology and Art: American Victory at Princeton

The Internet is replete with accounts of what happened

after the fighting at the Clarke Farm (e.g., MountVernon.org’s 10

Facts about the Battle of Princeton), but for our purposes, it is

sufficient to note that Washington rallied the troops and went on to take

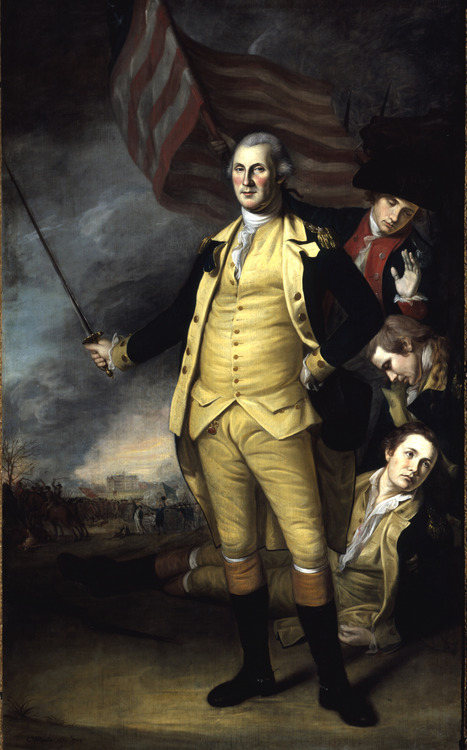

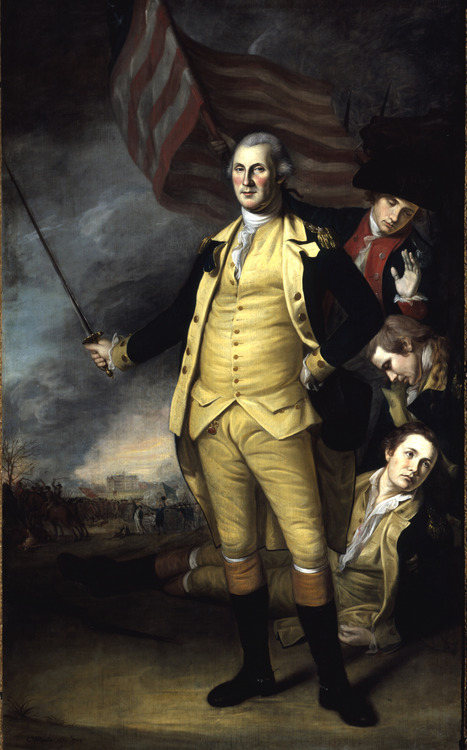

Princeton. This famous 1784 painting of Washington by Charles Willson Peale (a

Scots-American who fought with the militia at Princeton) shows the fatally wounded

Mercer lying at his feet:

29 [Image: 'George Washington

at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777’ (1784) painting, Princeton]

Click on the following hyperlinks to find more information

on the Thomas

Clarke House and the Princeton Battlefield.

A pdf from the Princeton Battlefield Trust about efforts to preserve the house

and the battlefield can be downloaded here.

You can also watch The Civil War Trust’s

'Campaign

1776’ video of the same aim: http://vimeo.com/111135230.

Marked 'College’ on the Cadwalader map, this building is

Princeton’s Nassau Hall, which was held by c.200 British Regulars when

Washington’s forces moved north after Mercer’s fatal skirmish. It can be seen

in the background of the Peale portrait. The damaged caused by the short

American siege which ended the battle can still be seen:

31 [Image: Nassau

Hall battle damage, Princeton]

Hugh Mercer: Burial(s) and Legacy

We know that Mercer speculated on lands in the west,

something confirmed by his holdings at his death. Embrey (1937: 122) reports Mercer’s

Will – dated March 20, 1776 – was 'probated in the Court House at

Spotsylvania, and is recorded in Will Book E, page 169’. Embrey’s work on

compiling the grantor index for the City of Fredericksburg can be accessed at

this searchable

webpage.

Mercer’s Will saw 2000 acres of land in Kentucky given to

his son William, and another to his 2000 acre package to his son George. His

son John got 3000 acres on the Ohio River, and his daughter Ann 1000 acres on

the Ohio River and another 1000 on the Miami River. A posthumous child was

given 2000 acres of Kentucky land, which was part of 5000 acres given to Hugh

by the Commonwealth of Virginia. Ann, William, John, and George also received

land in Stafford County opposite Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River that

Hugh Mercer had bought 'from General George Washington’.

Originally buried in Christ Church Burial Ground in

Philadelphia (in a funeral supposedly attended by some 30,000 mourners),

Mercer’s remains were transferred within the city to his current place of rest

in Laurel Hill Cemetery in 1840 by Philadelphia’s Saint Andrew’s Society, who

have the sword Hugh Mercer raised toward the Regulars as he was cut down. Shown

below, it was presented to the society in 1841, Mercer joined it in 1757, by

the granddaughter of the Continental Army’s Surgeon-General, Dr. John Morgan

(who, like everyone else at the battle, also studied medicine at Edinburgh in

the 1660s). Morgan received

it from Mercer at Princeton:

32 [Image: Hugh Mercer’s Princeton

sword, St Andrews’s Society]

There remains nothing left for me to say about the

remarkable Hugh Mercer, except leave you with the words written

in 1777 by Congress and, finally, erected with his Fredericksburg statue in

1902:

Sacred to the memory of HUGH MERCER, Brigadier-general in the Army of The United States. He died on the 12th of January, 1777,

of the Wounds he received on the 3rd of the same month, near Princetown, in New Jersey, Bravely defending the Liberties of America. The Congress of the United States, In testimony of his Virtues, and their Gratitude, Have caused this Monument to be Erected’

Internet Sources (at least, the ones I remembered to note down)

The

life of General Hugh Mercer: with brief sketches of General George

Washington, John Paul Jones, General George Weedon, James Monroe and Mrs. Mary

Ball Washington, who were friends and associates of General Mercer at

Fredericksburg: also a sketch of Lodge no. 4, A.F. and A.M., of which Generals

Washington and Mercer were members: and a genealogical table of the Mercer

family, by John T. Goolrick (1906)

History of

Fredericksburg: The History of an Old Town, by John T. Goolrick (1902)

The

Kittochtinny Magazine: A tentative record of local history and genealogy

west of the Susquehanna. v. 1, Jan.-Oct. 1905. Chambersburg, Pa.: G.O.

Seilhamer (1905)

Patriot-improvers:

1743-1768, by Whitfield Jenks Bell (1997)

Liberty’s

Fallen Generals: Leadership and Sacrifice in the American War of

Independence (Military Profiles) Steven E. Siry (2012)

The Glory of America: Comprising

Memoirs of the Lives and Glorious Exploits of Some of the Distinguished

Officers Engaged in the Late War With Great Britain, by R. Thomas (1837)

Essays

on David Hume, Medical Men and the Scottish Enlightenment: Industry,

Knowledge and Humanity (Science, Technology and Culture, 1700-1945), by Roger

L. Emerson (2009)

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=20020524&id=B_EyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=pggGAAAAIBAJ&pg=4358,7312492

(Goolrick’s grandson’s article)

Washington’s

Partisan War, 1775-1783 By Mark Vincent Kwasny (1998)

The

American Generals, John Frost 'Hugh Mercer’ (2012)

https://archive.org/stream/pottersamericanm03lossuoft#page/484/mode/2up

http://www.swordforum.com/forums/showthread.php?5913-A-real-Scottish-American-Hero

http://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/ten-facts-about-the-revolutionary-war/10-facts-about-the-battle-of-princeton/#TodayInHistory

https://blogs.princeton.edu/graphicarts/2011/06/the_death_of_mercer_at_the_bat.html

http://www.clanmunro.org.uk/hughmercer.htm

http://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/bios/Mercer__Hugh.html

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/hugh-mercer-dies-from-wounds-received-in-battle-of-princeton

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/army/p/mercer.htm

http://militaryhistory.about.com/od/battleswars16011800/p/monogahela.htm

http://www.nps.gov/fone/braddock.htm

http://www.revolutionarynj.org/revolutionary-neighbor/bios/hugh-mercer.pdf

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1750-1775/french-indian-war

Princeton Battle Field - http://www.state.nj.us/dep/parksandforests/parks/princeton.html

Thomas Clarke House - http://www.visitprincetonbattlefield.org/visit-princeton-battlefield/clarke-house-history/

http://www.revolutionarynj.org/revolutionary-neighbor/bios/hugh-mercer.pdf

The

Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783, John E. Selby (2007)

Biographical Monographs

English, Frederick. General

Hugh Mercer, Forgotten Hero of the American Revolution. New York: Vantage, 1975

Goolrick, John T. The

Life of General Hugh Mercer. New York: Neale, 1906.

Waterman, Joseph M. With

Sword and Lancet: The Life of General Hugh Mercer. Richmond: Garrett &

Massie, 1941.

Acknowledgements and Thanks

Thanks to Roy

Edwards, Kara Kozikowski, and my friend

and colleague Dr. Jen Novotny

for kindly allowing me to use their photographs and for their encouragement. I

also had a lovely phone call with Genevieve Bugary at Hugh Mercer’s Apothecary

Shop.

M.R. Wood, Dr. Elizabeth Pierce, Dr. Ryan K. McNutt , Dr.

Terence Christian, and my mother Marjory Horne were the brave souls who

proof-read the text.

Thanks also to Dr. Adrian Maldonado and Christy McNutt for technical **advice **on formATTing.

As they say, all remaining errors and omissions are the

result of my small brain.

Comments and Corrections

Please write to me, Dr. Tom J. Horne, via lovearchaeologymagazine@gmail.com

(If you get this far, you’re my hero. Thank you)